Rice: Noun or Verb?

Ricing, in the Linux community, is the practice of configuring a system to match the user’s aesthetic or functional goals. Ricing is primarily achieved through theming UI elements according to a desired look, though users frequently receive praise for other customizations, including niche or rare operating systems, shells, and window managers.

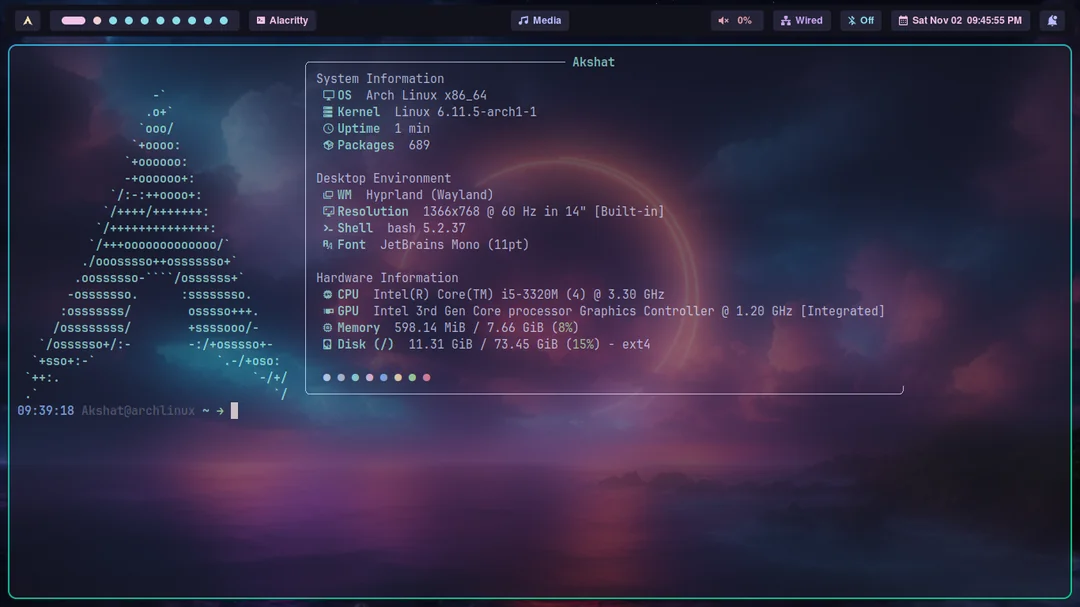

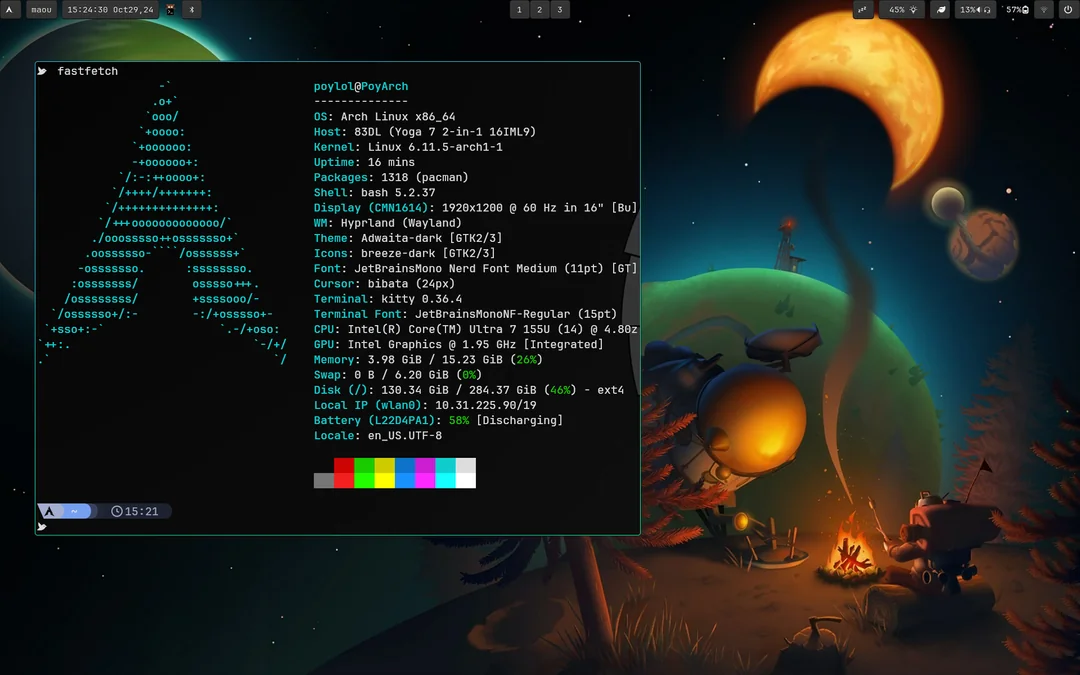

r/unixporn is the de facto home for “ricing,” on the internet, with 500K members as of writing. r/unixporn is a diverse collection of both the beautiful and the ugly in the ricing community. Making an aesthetically pleasing “rice,” these days is not particularly difficult. Window managers like Hyprland, provide built-in support for so-called “eye candy.” Hyprland comes out of the box with see-through blurred windows, smooth animations, shadows, rounded corners, and standard window management features that automate window placement according to specified layouts, allow for multiple workspaces, and provide keyboard shortcuts for moving between and transforming windows. Since Hyprland’s release, r/unixporn has become inundated with cookie-cutter “rices:” Hyprland + Arch Linux + Wayland, and call it a day. Here are a couple of examples of such rices:

| Hyprland Setup A | Hyprland Setup B |

|---|---|

|  |

To the untrained eye, these setups look noticeably different. However, the specification readouts on both terminals betray their similarity: both use Arch Linux, both use Wayland with Hyprland, both use Bash, and both use the JetBrains Mono Nerd Font. Unfortunately, these two setups are far from outliers in the r/unixporn community. r/unixporn, much like other subreddits, follows noticeable arcs in trends, with new metas arising and dying every few months. Yet, an overarching theme in the community that has persisted since I’ve been in it, is its preference for form over function.

Arch Linux kind of Sucks

I, as many other Linux users do, follow a predictable pattern of reconfiguring my system every few months or so. After I graduated from using Ubuntu, I felt obligated to try out every Linux distribution–different packagings of Linux which come with various built-in software like package managers, desktop environments, and init systems, among others. One month I would be using Kubuntu, the next I’d be using Gentoo, and the next I’d be using Arch Linux. Arch Linux was eventually the distribution I settled on for a while.

Arch Linux prides itself on being a relatively “bloat-free,” operating system, coming without a user interface to install the system. Users of Arch Linux are entrusted with manually installing the operating system from a tty–a bare text terminal environment. I enjoyed Arch Linux for a while due to its agnostic approach towards user setups–Arch makes no assumptions about what desktop environment you want to use, what window server you want to use, what window manager you want to use, what file system you want to use, among others. As a result, Arch Linux setups tend to be very lightweight, with low idle memory usage, and a low install size. Arch Linux also comes with a very diverse package ecosystem, with many niche applications available through pacman, Arch Linux’s built-in package manager, or the AUR, where users can submit their packages.

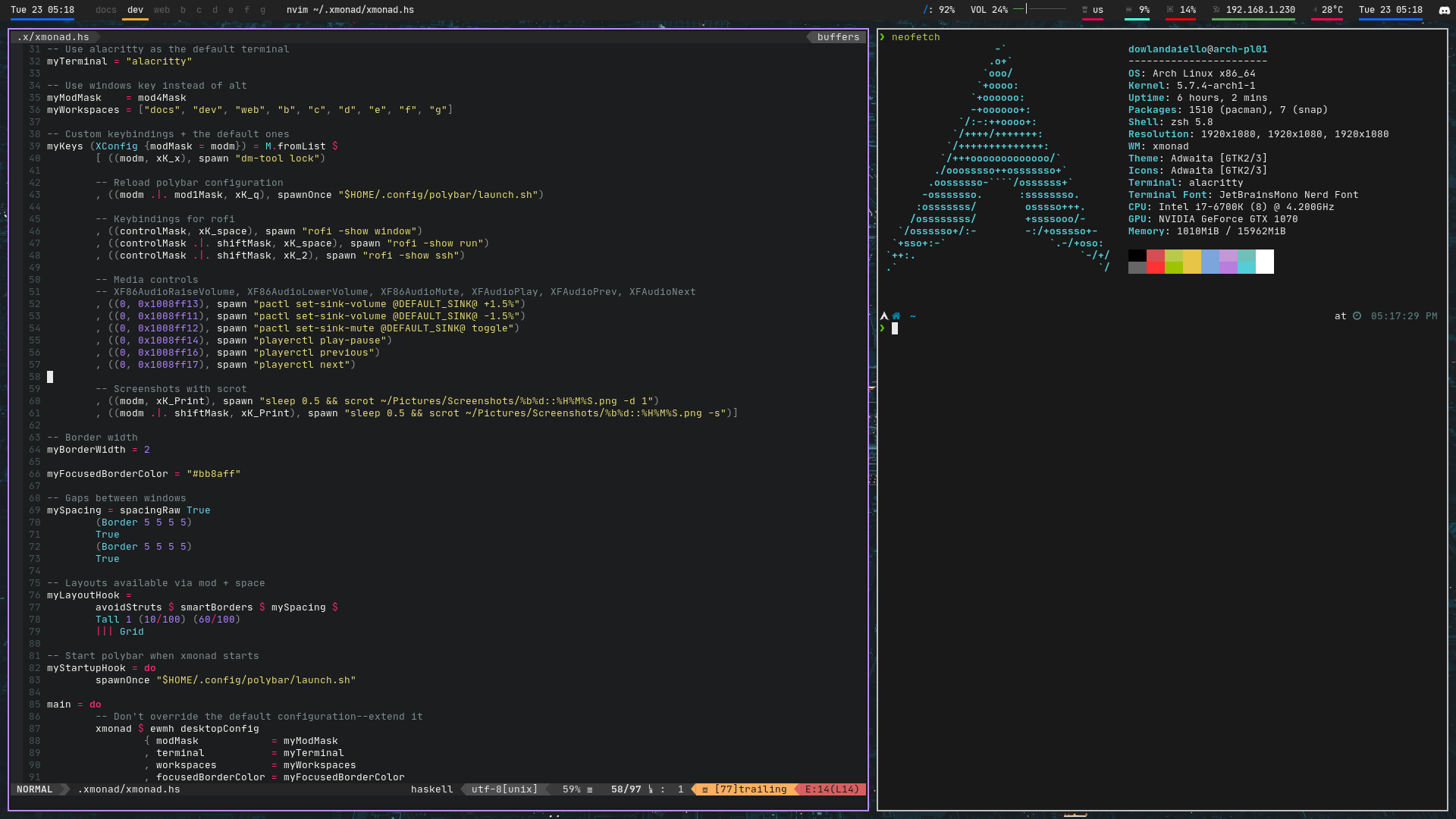

My experience with Arch Linux was generally pleasurable. My system felt snappy, my memory usage was low, and my system did what I wanted–no more, no less. Here’s what my system looked like:

I stuck with Arch Linux for about 3 years. Over those few years, I re-riced my system a few times, changing only the color scheme, and leaving the rest of the system intact. However, I grew increasingly displeased over time with a predictable pattern that emerged. Every time I updated my system, about every 3 weeks or so, my computer would have about a 70% chance of breaking, causing me to spend at least two hours browsing the Arch Linux forums looking for a solution. Frequently, this would be caused by a corrupted GPG key, dependency conflicts between packages, or installation scripts overriding my manual hacks for my system. In the worst-case scenario, my entire bootloader would become unusable, causing my system to boot into an “emergency shell,” permitting almost no recovery features. Something had to change.

Nix: Language, Package Manager, Operating System, and Infrastructure As-Code

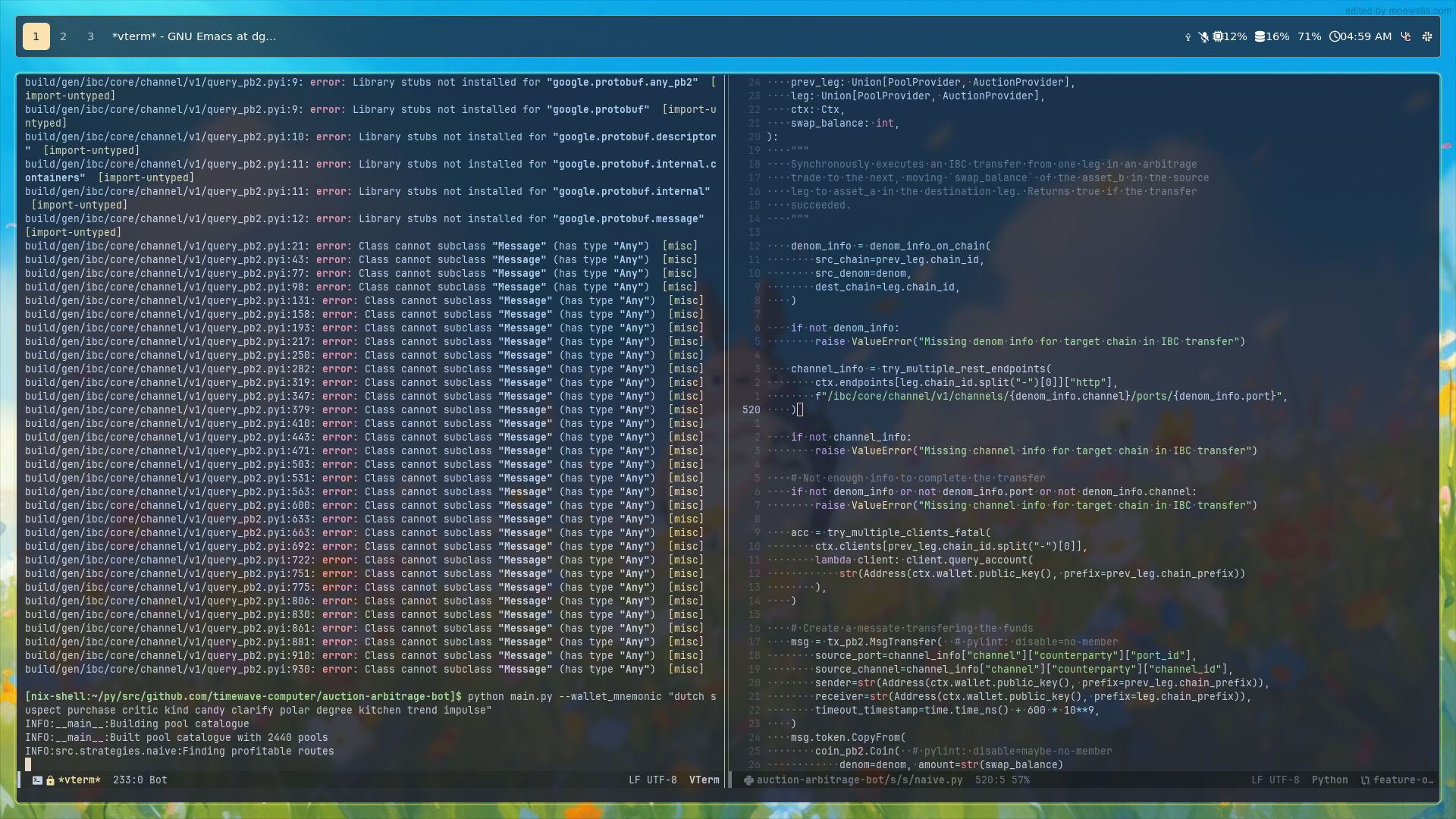

About seven months ago, I started a new job at a cryptocurrency startup as a Rust software engineer. My first project, an MEV searcher for the Cosmos network, involved an extremely diverse stack, including Python, Rust, protobuf, Docker, WASM, and other disparate components. Development became arduous over time as more and more components were added. Furthermore, it became increasingly unportable, with installation processes differing between MacOS, and Linux distributions. To make matters worse, updating the project’s installation instructions became a difficult task due to how quickly the project was changing. This resulted in great difficulty onboarding other team members, who would have to follow a 20-step-long installation process to get the development environment set up.

As a member of r/unixporn, I inevitably stumbled upon NixOS. NixOS, as far as I was concerned at the time, seemed like the next level of Linux autofellatio. NixOS users, in my eyes, were superior to Arch Linux users, though I wasn’t sure exactly why. After doing preliminary research, I discovered that NixOS came with myriad benefits compared to other operating systems: configuration was highly centralized in, at one extreme, a single configuration file, and the OS was highly portable and highly reproducible.

As are all operating systems, NixOS is differentiated by its unique package manager: Nix. Nix, unlike other package managers, emphasizes package isolation, reproducibility, and portability of package building. Nix packages are defined by their build processes, build dependencies, and runtime dependencies, which are specified in “derivations.” Derivations are written in the functional Nix language, which allows for expressive and readable code defining packages. Here is an example of a simple derivation for a website made with Jekyll:

with import <nixpkgs> {};

stdenv.mkDerivation {

name = "example-website-content";

# fetchFromGitHub is a build support function that fetches a GitHub

# repository and extracts into a directory; so we can use it

# fetchFromGithub is actually a derivation itself :)

src = fetchFromGitHub {

owner = "jekyll";

repo = "example";

rev = "5eb1b902ca3bda6f4b50d4cfcdc7bc0097bac4b7";

sha256 = "1jw35hmgx2gsaj2ad5f9d9ks4yh601wsxwnb17pmb9j02hl3vgdm";

};

# the src can also be a local folder, like:

# src = /home/sam/my-site;

# This overrides the shell code that is run during the installPhase.

# By default; this runs `make install`.

# The install phase will fail if there is no makefile; so it is the

# best choice to replace with our custom code.

installPhase = ''

# Build the site to the $out directory

export JEKYLL_ENV=production

${pkgs.jekyll}/bin/jekyll build --destination $out

'';

}

from nix-articles on GitHub

Of note in this derivation is the source, which is linked to a specific version of a specific GitHub repository. Furthermore, a hash is provided, which uniquely identifies the content of the GitHub repository, and ensures that it will always be the same. Finally, the build script requires no steps to install Jekyll, which it uses to build the site, and defers to Nix to automatically install the package from the Nix package repository, nixpkgs. The result is a highly predictable build process that requires only one command to install, depending on where the package is used–nix-shell, if used in a development shell environment, or nixos-rebuild switch if installed as a system package. These advantages appeared to me to solve all my woes with onboarding team members into a highly complex development environment. And, by the grace of God, they did.

Fearless Ricing

A few months into my new job, I was tasked with assisting team members with installing my application. The two team members had MacBooks, so I advised that they use Nix to install the package, as it would be much easier than manually completing the installation process. After installing Nix, I instructed my team members to run a single command in the repository: nix-shell. After about 5 minutes of installing the packages, I instructed them to start the application. No errors arose, and my venture into Nix in the team was vindicated.

With time, I grew curious about whether Nix’s advantages, specifically reproducibility, could aid in making my system more stable. Theoretically, since Nix allows packages to be built in isolation, and pins dependencies to specific commits via lockfiles with a feature called flakes, I would never have to worry about my system breaking ever again. So, I took the plunge and followed a tutorial on setting up NixOS on my machine. The process took about an hour to get a running install, and a couple of days more to get to a “rice,” I liked. Throughout the process, I experimented with different window managers, different window servers, and different configurations. Unsurprisingly, I stumbled along the way. My configs would have syntax errors, my scripts would have typos, etc. However, unlike with Arch Linux, I didn’t worry once about getting stuck in an emergency shell. Every time my system booted, I was greeted with the option of booting into my system from a specific version of my configuration, dating from the first working setup I had installed to the latest broken setup I experimented with. The result was rapid, fearless prototyping.

To this day, in the 6 months or so that I’ve been using NixOS, I have never had to start from scratch or spend hours at a time debugging my system out of necessity. Now, when I spend hours hacking away at my configuration, it’s voluntary.

Form or Function: Pick Two

As expected, I fell for the appeal of glossy terminals with rounded corners. I believed that if my everyday experience using my system evoked a sense of aesthetic pleasure, I would be happier doing everything on my computer. For a while, this was the case. Here’s what my setup looked like:

Without a doubt, should I have posted the setup on r/unixporn, I would have received similar criticism that I described before: “Wayland + Arch Linux + Hyprland, and call it a day.” However, I was pleased with the look of my system. My system was designed for me, and me alone, and my goal at the time was to maximize aesthetic pleasure. However, with time, my system grew increasingly sluggish. Animations felt slow, my idle memory usage was high, I had enough packages installed on my system to fill up half my hard drive, and I felt embarrassed every time I had to confess my system had no screen-sharing features. Something needed to change.

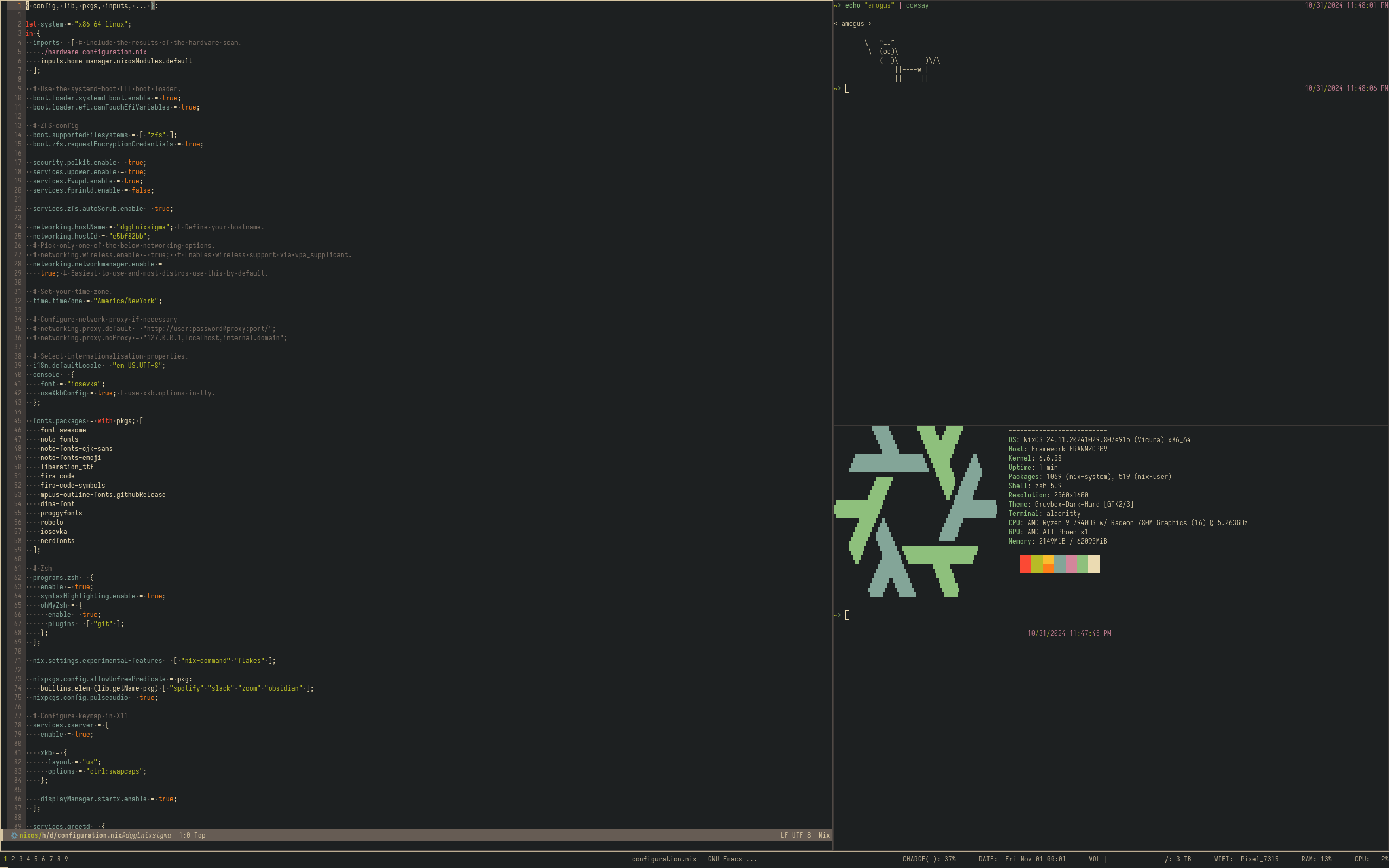

A week ago, I decided to change my ricing goals to maximize productivity. So, I set to work redesigning my system. My new configuration uses a custom window manager written in Rust with the penrose library, which is a pleasure to work with, Xorg, which permits screen-sharing, polybar, with as few modules as possible, and a TUI greeter, which boots extremely quickly. The result is a blazingly fast system, which allows me to work as fast as my mind and fingers will permit. Here’s what it looks like:

The whole way along creating my new rice, despite any issue I ran into, I could rest easy knowing my system would always remain intact and usable.

Every day I use my computer, I fall in love with NixOS and Nix again, and if you give it a try, I think you will, too, no matter if you prefer form or function.

P.S.: This site is built and deployed with Nix ;)