Lambda Calculus: Part II

As I recounted in my previous post, I’ve been enthralled in studying higher-level CS in my free time. Lambda Calculus has long been a particular interest of mine, so I recently took to writing a Lambda Calculus interpreter. The interpreter takes in a lambda expression and attempts to reduce it, step by step, or to infinity–or termination. As usual, I grew bored with the project with time and eventually decided I was content with its degree of completion and correctness. As of writing, the interpreter can reduce church encoded arithmetic and list expressions, and attempt to reduce the paradoxical combinator, step by step, or by causing a stack overflow. Surprisingly to those who will peruse the source code, almost all of the components are handwritten. It uses no parsing libraries and has no dependencies, aside from, implicitly, Rust’s standard library. This was a mistake.

Parsing is Hard

Parsing is, in short, the art of edge case handling, and by nature, results in very verbose, unreadable code. In the experience I gleaned from writing lci, I’ve determined that hand-writing parsing solutions, in almost all cases, will likely make the task of parsing even harder and unsustainable.

Edge cases, tautologically, require special consideration. This is especially true for hand-written solutions like mine, which do not defer to any dependencies. When none of the work to handle special cases is done for you, you must do the work yourself. So that is what I did. The result was a disgusting, abhorrent amalgamation of string manipulation and pattern matching, which bears resemblance to code written by a monkey engaged in proving the Infinite Monkey Theorem in its intelligibility.

Exhibit A: Cyclomatic Complexity Ad Infinitum

At the top level, a lambda expression can only be one of three things: a variable, an abstraction, or an application. These terms are explained in my previous post for those who are interested, but for the purposes of this article, their significance is irrelevant. This would seemingly imply that parsing a lambda expression would involve invoking one of three possible parsers: a variable parser, an abstraction parser, or an application parser. Each is distinct in that abstractions begin and end with parenthesis, applications involve one or more expression next to each other, and variables are just letters. It escapes my understanding, then, why my parser contains 8 if clauses, two pattern matches, and interior calls to further parsing functions.

To elucidate this dilemma, here’s an example of deeply nested control flow in the parser:

let mut applicands = to_curried(tok_stream)?;

// Single term

if applicands.len() == 1 {

let mut term = applicands

.pop()

.ok_or(Span::new(0, Error::EmptyExpression))?;

// Free term

if term.len() == 1 {

let tok = term.remove(0);

match tok {

Span {

pos: _,

content: Token::Id(c),

backtrace: _,

} => {

return Ok(Expr::Id(c));

}

Span {

pos,

content,

backtrace: _,

} => {

return Err(Span::new(pos, Error::UnrecognizedToken(content)));

}

}

}

/// cont...

This code parses a free variable. That is to say, special case handling is exceedingly verbose without readily available, composable units which do the work for you. These readily available, composable units are frequently referred to as combinators, and I like them, a lot.

Enter Chumsky

Continuing my foray into CS self-study, over the last two weeks, I’ve been implementing a general interaction net reducer. The reducer takes inspiration from a proposed intermediate language representing interaction net rules and active pairs from a paper, “Compilation of Interaction Nets,” by Hassan et al.

Here’s an example of a program written in the language:

Add[x, y] >< Z => x ~ y

S[x] >< Add[y, z] => Add[y, S[z]] ~ x

Add[Z, y] >< Z

This program represents rules for evaluating addition, as well as an active active pair adding zero and zero together.

Thanks to a library I discovered through crates.io called Chumsky, writing a parser for this language was exceedingly straightforward, and maintaining the parser code is painless and worry-free.

Combinators for Humans

Chumsky is a parser combinator library for humans. For the uninitiated, this statement seems vacuous and performative. But for programming language nerds who have used Chumsky, it rings true.

Chumsky has an initial learning curve to surmount that comes with any declarative style to writing parsers. However, the learning curve is extremely mild, and for anyone who has used Rust and is familiar with its Iterator API, is almost nonexistent.

Chumsky comes with great documentation, and simple, intuitive, and clearly named utilities for parsing common expressions–like C-style identifiers, digits, parenthesis, and commas, among others. Take, for example, my parser for an agent (e.g,. Add[x, y]) in my language:

let active_pair_member = recursive(|input| {

let agent = text::ident()

.try_map(|s: String, span: <Simple<char> as Error<char>>::Span| {

if s.chars()

.next()

.map(|c| c.is_uppercase())

.unwrap_or_default()

{

Ok(s)

} else {

Err(<Simple<char>>::custom(

span,

"agent names must be capitalized".to_owned(),

))

}

})

.then(

input

.separated_by(just(',').padded())

.delimited_by(just('['), just(']'))

.or_not(),

)

.map(|(name, inactive_vars)| ActivePairMember::Agent {

name,

inactive_vars: inactive_vars.unwrap_or_default(),

});

let var = text::ident().map(ActivePairMember::Var);

choice((agent, var))

});

Aside from the custom logic for parsing specifically uppercase identifiers, which could be replaced with a single call to text::ident(), should lowercase prefixes be permitted, the parser is exceedingly short and readable. From a high level, it attempts to parse the input as an uppercase identifier, then parses further agents or identifiers surrounded by square brackets and delimited by commas. This is, by any means, a massive improvement from the hand-written parser I wrote for my lambda calculus interpreter.

Maintainabilitymaxxing, UXmaxxing

Adding new features to parsers written in Chumsky is extremely straightforward. Chumsky is integrated with the Rust type system, so any changes must comport with the design of Chumsky’s existing combinators, and your language design. For example, you cannot map a single expression to a vector of AST elements, lest the compiler berate you for your gross negligence.

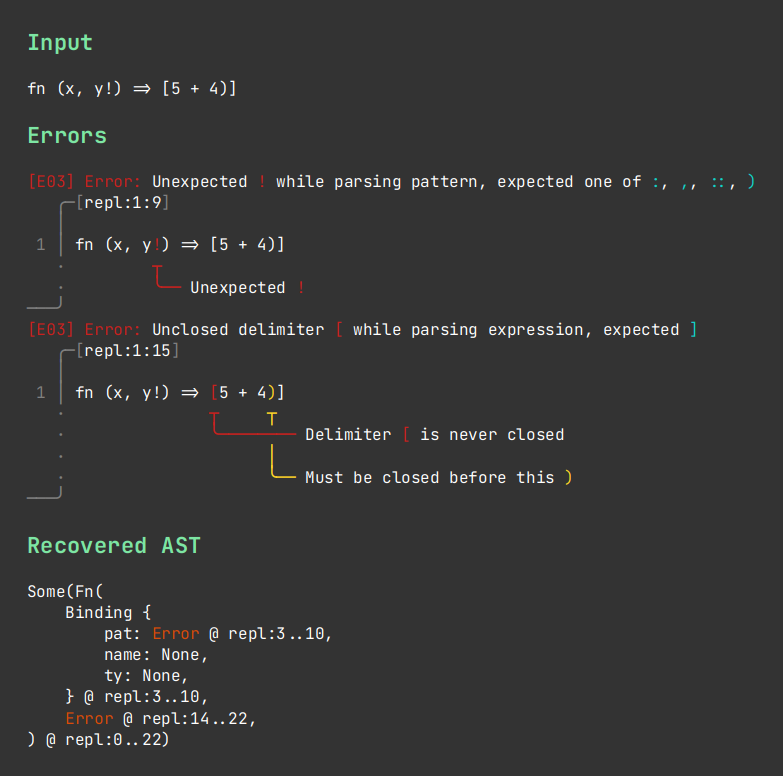

Furthermore, parsers written with Chumsky are very user friendly, since they provide robust error handling, which can be easily integrated with existing compiler diagnostic libraries for error messages like this error message provided by Ariadne:

I’m nowhere near done with my interaction net reducer, but I am long done with writing the parser, thanks to Chumsky. For anyone who is considering writing a language and, perhaps a parser, for whatever masochistic reason, give yourself some grace, and try out Chumsky.